If you share my interest in the subject of child prodigies, I’d probably start by referring you to this article by Edward Winter.

One name missing from this article, though, is that of Harry Jackson, who, in the late 1870s, was billed as the Yorkshire Morphy.

You might have met him briefly in my previous Minor Piece, but I’m sure you want to know where he came from, and what happened next.

Our story starts in what was in the 19th century the thriving mill town of Dewsbury in West Yorkshire, south of Leeds and Bradford, north east of Huddersfield.

Among those working in the cloth industry in the middle of the century was John Jackson. He and his wife Hannah had four sons and a daughter. While two of his sons, Samuel and Joshua, graduated into the middle classes, becoming solicitor’s clerks, the other boys pursued different careers. Abraham worked as a labourer before emigrating to Canada where he became a farmer. John, the youngest son, became (like my paternal grandfather in Leicester) a painter and decorator.

It was John who was the chess player, although I’d guess the whole family played socially. He and his wife, another Hannah, had a large family, three of whom played competitive chess. Harry, the Yorkshire Morphy, was his oldest son, born 16th December 1863. We’ll return to him later.

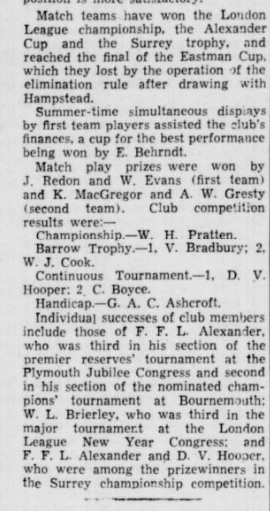

The next chess player in the family was William Ewart Jackson (1867-1951), his name suggesting that the family were supporters of the Liberal Party.

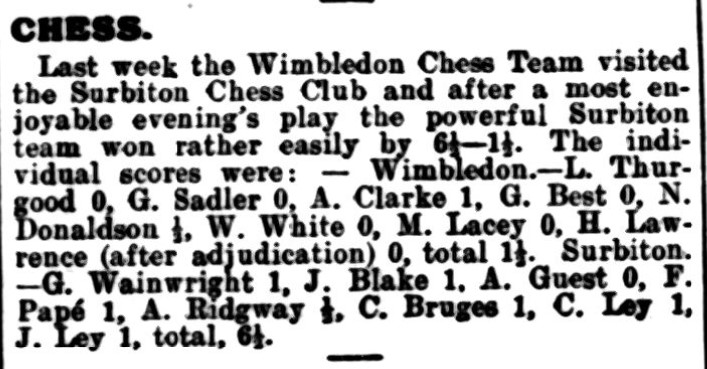

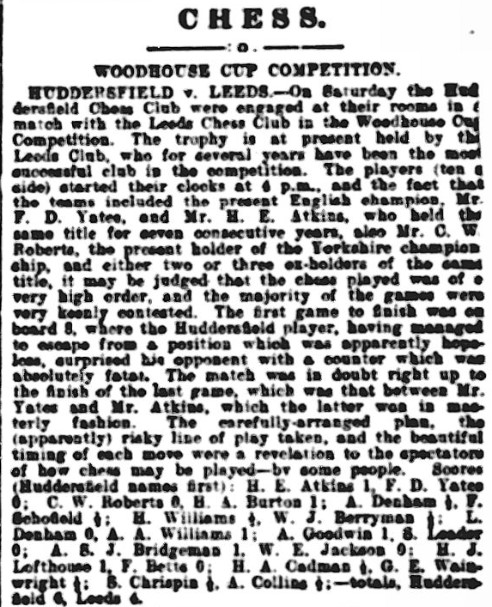

William (known as Willie) played for Dewsbury in the 1880s before moving to Leeds, where he worked for William Pape, a firm of glass merchants, and joining the local club. He was active in Leeds chess, both over the board and correspondence, until at least 1918.

In what may have been one of his last matches (the Woodhouse Cup was suspended between 1916 and 1919) he was privileged to watch Atkins beating Yates in masterly fashion on top board.

Here are two games. Click on any move in any game in this article for a pop-up window.

White unnecessarily sacrificed a piece on move 39 when he might have held by going after the a-pawn.

The youngest of the chess-playing Jackson brothers was Joshua (1878-1935).

Joshua had an unusual competitive chess career, most of it taking place towards the end of his life.

There’s a J Jackson playing alongside Harry for Dewsbury in 1889, but it’s not clear whether this was John or Joshua.

It seems, though, that he only really started to take chess seriously after the First World War. In 1921 he entered the Yorkshire Championship, and also ventured to Manchester for the Northern Counties championship, where he was rather out of his depth, scoring only 1/7 against opponents such as Yates and Wahltuch, who shared first prize.

He was also playing correspondence chess, in 1922 winning his game for Yorkshire against Eric Augustus Coad-Pryor, whose father was at the time Vicar of Hampton Hill.

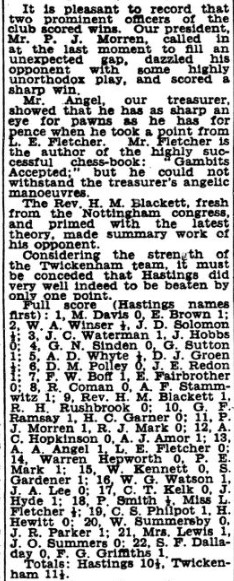

In 1923 he played again in the Northern Counties Championship, this time in Liverpool. That year the top section was a strong master tournament headed by Mieses, Maroczy, Thomas and Yates. Joshua played in the Major section, scoring 4½/9. Much interest was caused by the participation of 15-year-old Gerald Abrahams, who beat him in the first round.

In 1925 Scarborough Chess Club decided to run what they hoped would be the first of an annual series of tournaments over the Whitsun holiday. Joshua entered the major tournament, which was split into A and B sections along with another group for late entrants. The top two players in each section advanced to the play-offs.

Not all the results were recorded, but we know that he drew with Frank Schofield of Leeds, who won both his section and the play-offs, and beat both Sydney Meymott and Stephen Ludbrooke of Rotherham. As he didn’t qualify for the play-offs, I’d guess he may well have been third in the Major A section. A highly commendable result for someone in his late forties with, as far as I can tell, little competitive experience.

The 1926 Scarborough tournament was graced by the presence of the great Alekhine, who duly won the top section. Joshua again played in the Major, this time coming second to Edith Holloway in his section, and, second again in the play-off for 4th, 5th and 6th places. There were always several ladies competing in Scarborough.

I note that J Jackson of Dewsbury’s Yorkshire Terriers won a lot of prizes in the Belfast Dog Show that year. Is this also Joshua, I wonder?

He didn’t take part in 1927, but was back again in 1928, scoring 5/9 in his section of the Major tournament.

In 1929 they were struggling for strong players, due, in part, to the local corporation withdrawing their support, so the top section was very much a mixed affair. There were two genuine masters, Tartakower and Sir George Thomas, two strong amateurs in Harold Saunders and Victor Wahltuch, and four lesser players, one of who was Joshua Jackson. Unexpectedly, he had made the big time late in life.

While he was no match for the top players, he managed a win and two draws against the other lesser lights of the tournament, scoring a respectable 2/7.

The games were all recorded by Tinsley and have now been published in a book by Tony Gillam and by John Saunders (no relation to Harold) on BritBase.

Joshua played the Old Indian Defence too passively against both Saunders and Wahltuch and was duly squashed.

Here’s the Saunders game.

Against both Tartakower and Thomas he sacrificed a piece unsoundly thinking he was going to regain it but missing a fairly obvious tactic.

Here’s the Tartakower game.

He played out a steady, uneventful draw against Edith Holloway, concluding in a level pawn ending. Against Bolland he seemed to agree a draw in a winning position with two extra pawns.

His one win came from an instructive ending, when his opponent chose the wrong queen trade, going for a lost rather than a drawn pawn ending. There were further mutual blunders on move 42.

Among the other competitors was the 15-year-old Maurice Winterburn, also from Dewsbury, who may well have travelled there with Joshua.

Scarborough hosted the British Championships in 1930, although the championship itself was replaced by an international tournament. Joshua didn’t take part this time, but continued to play both over the board and by correspondence into the 1930s.

Chess was now becoming increasingly popular with teenage boys, and Joshua, as Dewsbury’s star player, served as a mentor to the youngsters coming through the door.

One of those was Maurice Child, who joined as a 15-year-old in 1932, and, 75 years later, had very fond memories of Joshua Jackson.

The outstanding personality between the two world wars was Josh Jackson. A fine player, among the top half-dozen in Yorkshire, and a great analyst. He was always ready to teach any young player and could play several games simultaneous and blindfold!

He was a barber and there was always on show in the shop a board with the latest position in his current correspondence game.

But it’s Harry you really want to know about, so we need to return to Dewsbury.

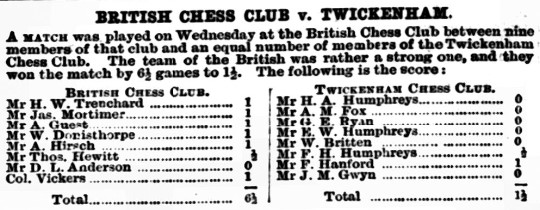

His father John first attended the annual meeting of the West Yorkshire Chess Association in 1876. Both John and Harry would also attend every year between 1877 and 1880.

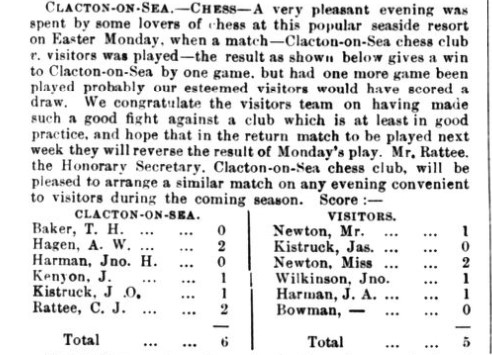

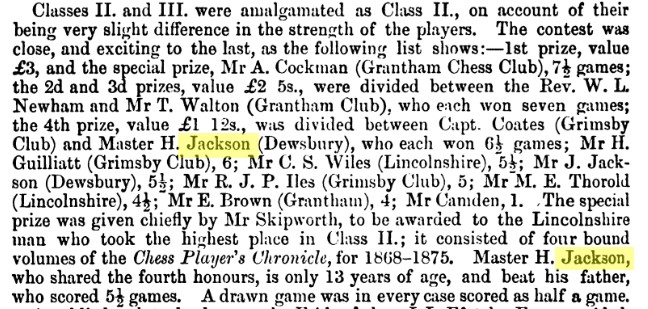

In January 1877 John and Harry travelled to Lincolnshire, both taking part in the Second Class section of the inaugural Lincoln County Chess Association meeting.

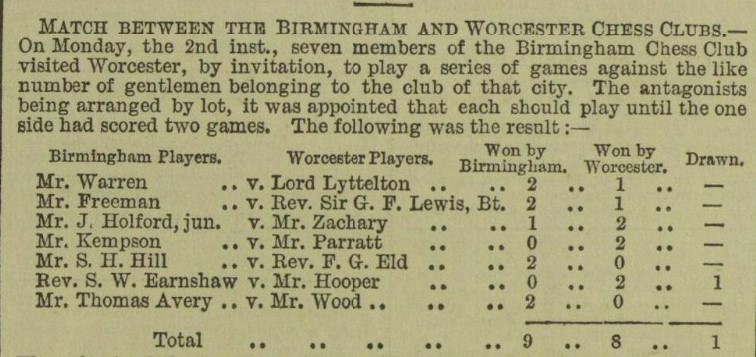

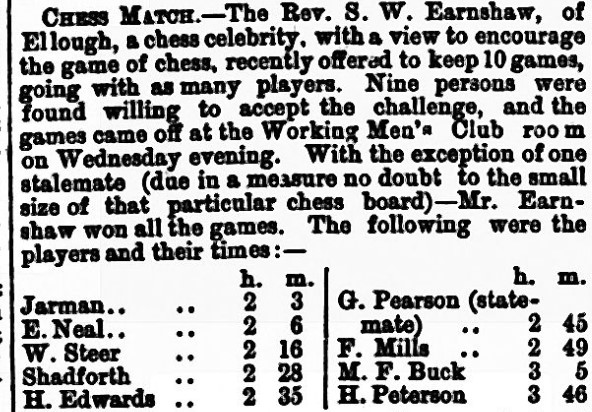

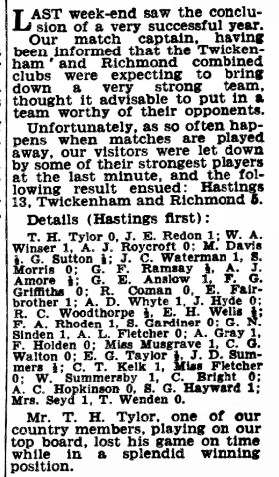

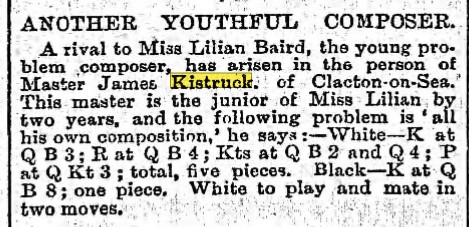

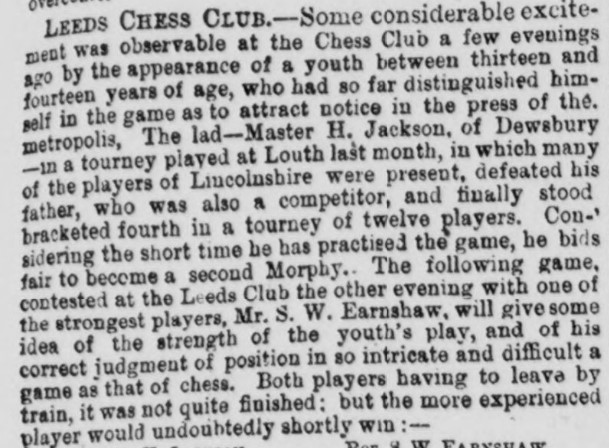

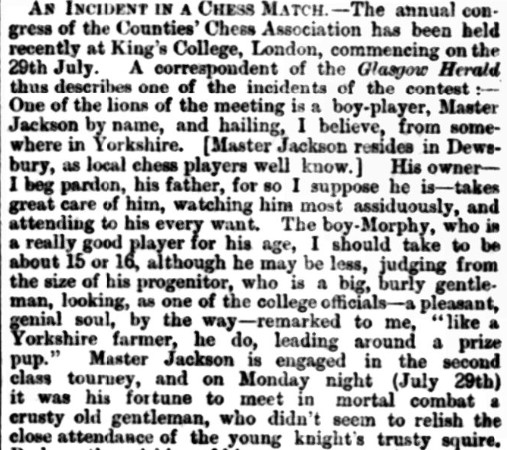

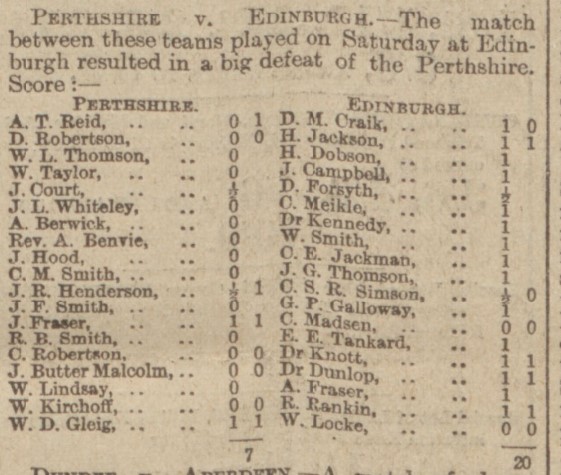

The Chess Player’s Chronicle reported on this event.

The Westminster Papers added that “Master H Jackson is a young gentleman of promise, aged 13, and is likely to be heard from again in the world of Chess”. For the winner, Abraham Cockman, see this discussion.

It’s easy to forget, in these days of pre-teen grandmasters, how unusual it was for even 13-year-olds to take part in chess competitions, and interesting to note how much attention young Harry received at the time.

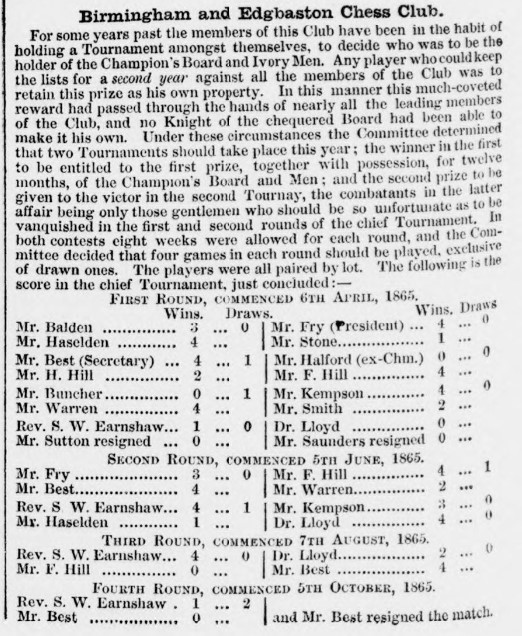

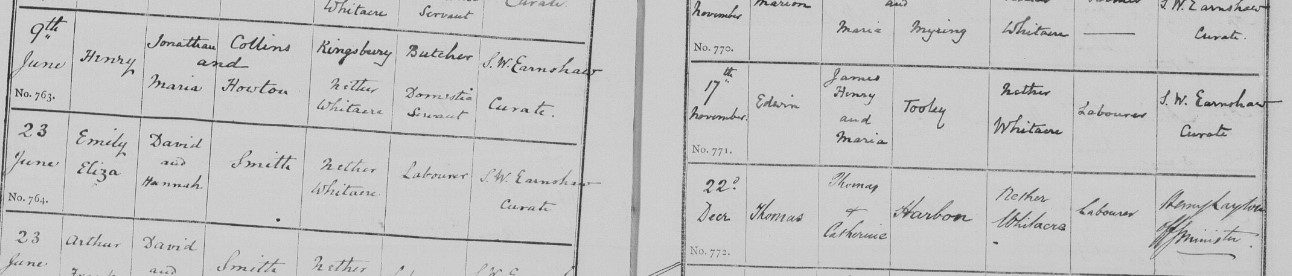

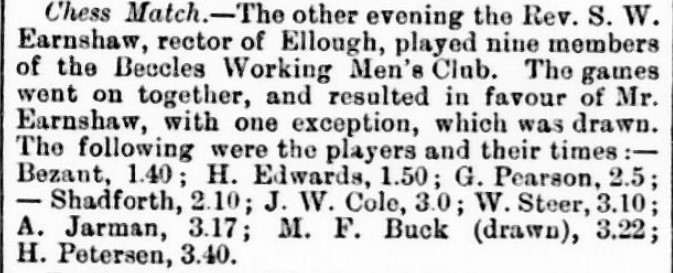

Inspired by this success, John was inspired to give young Harry a trial game against Samuel Walter Earnshaw at Leeds Chess Club a few weeks later.

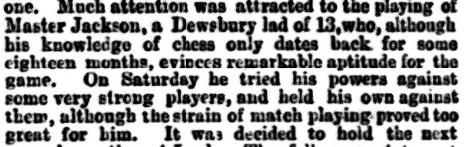

At the gathering of the West Yorkshire Chess Association, there was concern that the strain of match play was too much for one so young.

Try telling that to Bodhana or Ethan.

In December a delegation from Huddersfield Chess Club led by John Watkinson, who would found the British Chess Magazine in 1881, visited the Dewsbury Working Men’s Club to assess their chess players. Watkinson took on ten of them, including both John and Harry Jackson, in a simul.

Harry’s game was unfinished but Watkinson thought he could win. Stockfish agrees with his assessment.

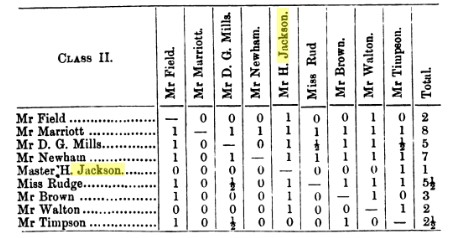

Harry played in Lincolnshire again over the New Year, but this time was less successful, as the Chess Player’s Chronicle reported.

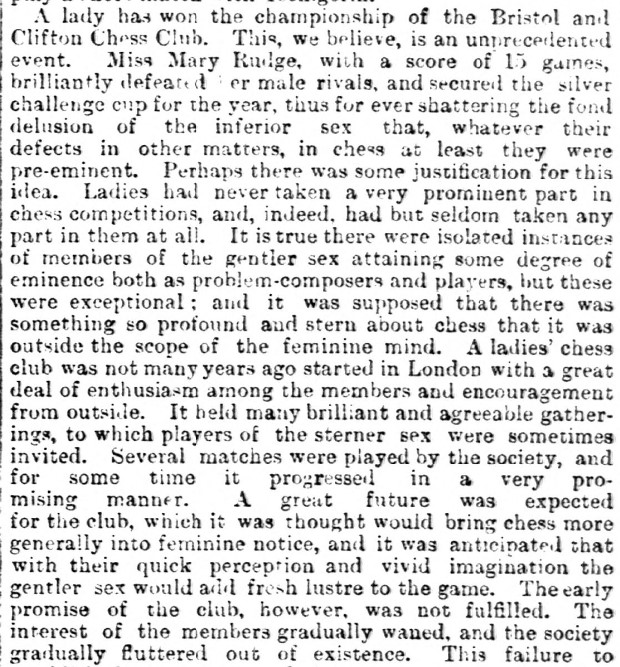

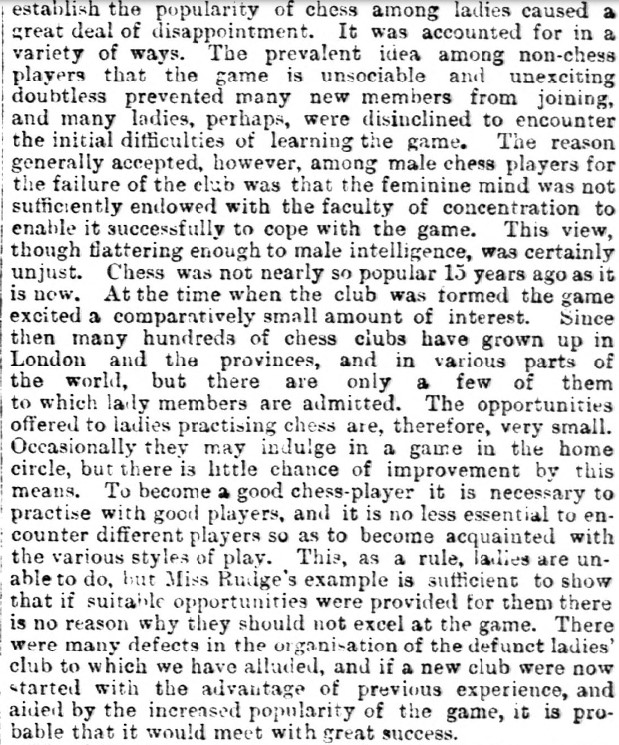

The winner was Thomas Walter Marriott, not, as was reported in some sources, Arthur Towle Marriott. You’ll also note that Mary Rudge finished 3rd.

An interesting feature of this event was a displacement tournament, where the bishops and knights started on each other’s squares, an early precursor of Chess960.

A chess club had now started in Dewsbury, with Harry finishing in second place in their first tournament, and playing on top board in their first match, against Huddersfield.

John Watkinson visited again for another simul: this time Harry put up rather less resistance, inadvisedly choosing an unsound gambit as early as move 2..

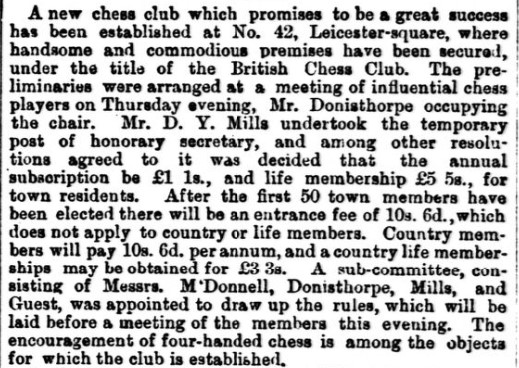

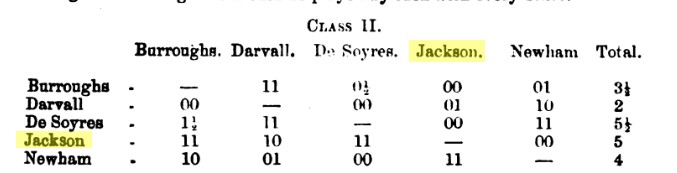

After winning a prize in the West Yorkshire gathering, Harry ventured to London for the Counties Chess Association meeting.

He did well to win both his games against Rev John De Soyres, a pretty strong player (2146 on EdoChess at the time), who would later emigrate to Canada. You can read more about him here.

In this game his opponent, whom I believe to be Frederick Orme Darvall, who had been Auditor-General of Queensland 1867-77, but was by that time living in London, overlooked a mate in one.

Harry’s participation must have caused quite a stir, not just because of his age but because of his background as the son of a painter and decorator from Yorkshire. It was also not without controversy.

I like the description of John here, who sounds very much like some (but, I hasten to add, not all) chess parents today.

After this trip to the capital Harry continued playing locally, and also by correspondence.

He lost this game against the blind player Henry Millard.

Stockfish thinks it’s mate in 15, not mate in 11, but never mind.

In November 1879 he took the top board in a match between Dewsbury and Wakefield, winning two games and drawing one against schoolmaster John William Young, who taught English and Music at Wakefield Grammar School. John played in the same match, on bottom board, but was only able to conclude one game, which he lost.

In this game Harry’s speculative sacrifice proved successful.

In 1880 Harry returned to Lincolnshire, this time to Boston, where he won the 2nd class tournament of the Counties Chess Association.

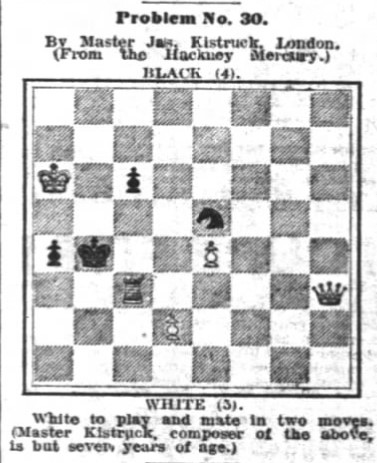

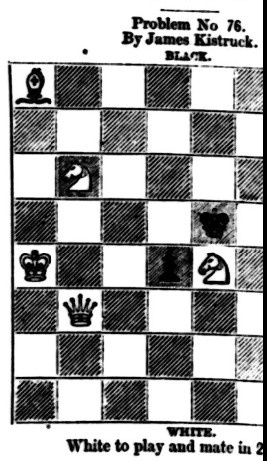

But now he was playing less as he’d taken up a new hobby: composing chess problems. Between 1879 and 1881 many problems bearing his name appeared in a wide variety of publications. Two of them even won first prizes.

Problem solutions can be found at the end of the article.

Problem 1. #3 1st Prize (London) Brief 1880.

Problem 2. #2 1st Prize The Boys’ Newspaper 1881.

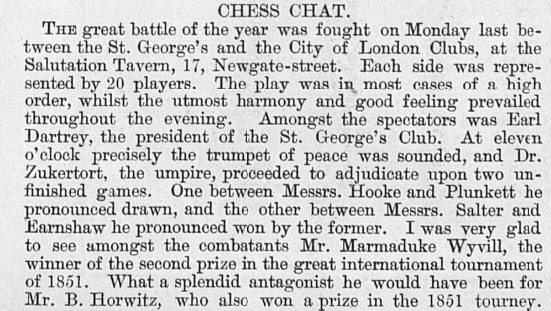

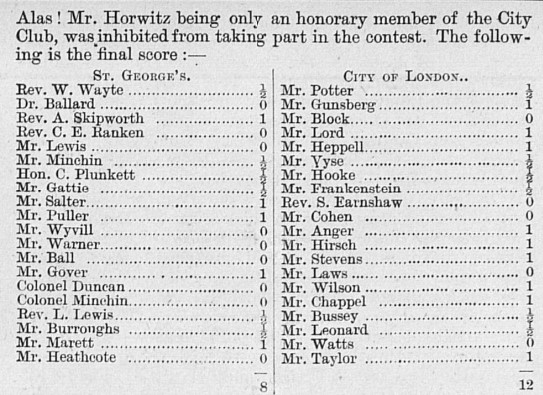

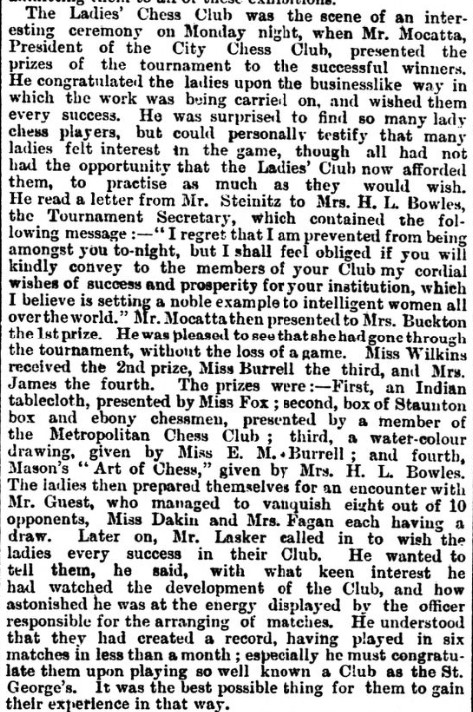

By 1881 Harry was living in London and involved with the City of London Club, taking on the role of librarian. In a match against St George’s he did very well to beat the very strong William Hewison Gunston 2-0. On 31st May the Chess Player’s Chronicle reported that ‘young Mr Jackson (lately Master Jackson of Dewsbury)’ had reached the last three in a handicap tournament before being eliminated.

I haven’t been able to locate him in that year’s census, but the rest of his family were all present and correct back in Dewsbury.

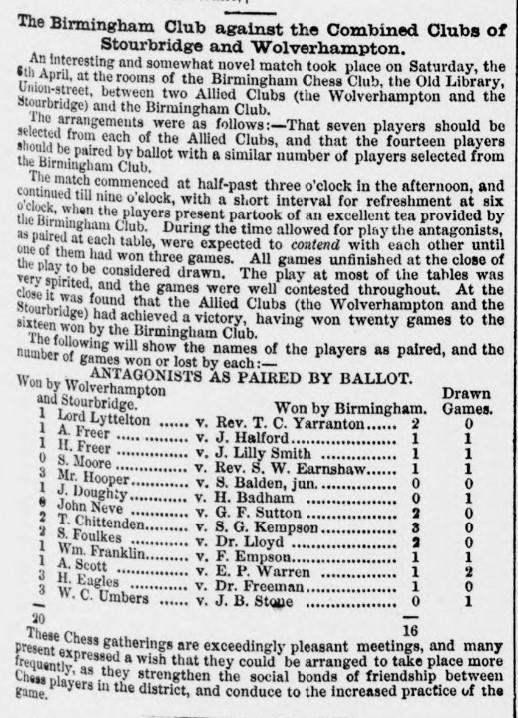

He remained in London for a few more years, playing, alongside his old friend Samuel Walter Earnshaw, in a simul against Mackenzie in 1882, and in 1883 beating Hugh William Sherrard in a match between the City of London 3rd team and Cambridge University, although he seems to have taken a break from composition.

At this point he may have moved back to Yorkshire. A couple of problems appeared in 1885, and then, in 1877, he turned up in York.

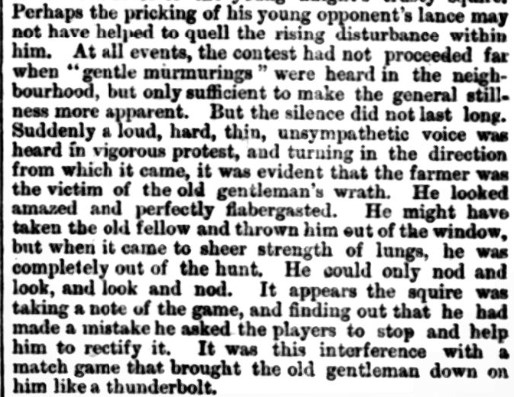

Here he is at their 1887 AGM, resigning as secretary and being appointed vice-president, as well as winning their club championship and guaranteeing himself top board for the next year. Although this is the earliest mention I’ve been able to find he must have been there for several months.

Later records give the club venue as at Mr Jackson’s Cocoa House in High Ousegate, suggesting that this was Harry’s occupation at the time.

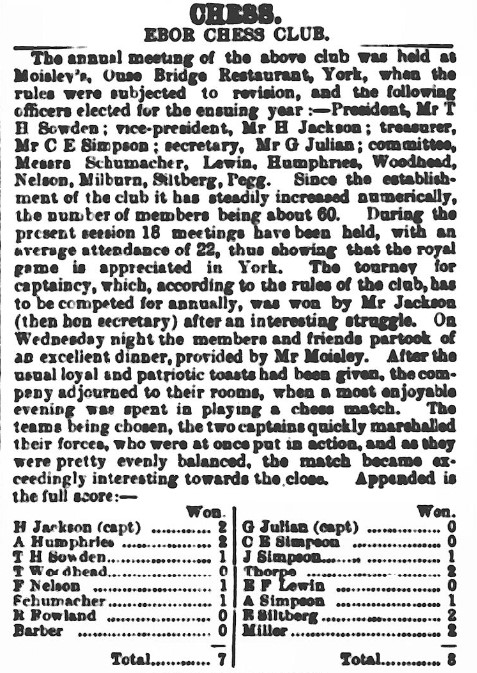

On 24 April 1889 the local unionist party held a major event. No less than 3000 people sat down for tea, followed by concerts, dancing, and a demonstration of living chess. Although this was not Harry’s party (he also played for York Liberals) he wasn’t above taking part. There was a pre-arranged game between two local dignitaries, and then a more serious game between Charles George Bennett and Harry Jackson.

The game was played to a pretty high standard considering the circumstances.

He had returned to the role of secretary of the Ebor Chess Club, but in 1890 he switched to the job of treasurer. The following year he resigned from that role and didn’t enter the club championship because he was away from home. But the 1891 census found him living in lodgings and working as a clerk, which suggests the cocoa house hadn’t been successful.

He continued to be very much involved with the Ebor club: as well as playing in matches he was giving regular simuls and lectures up until November 1894. After that, he seemed to disappear for a year or so.

In 1896 he turned up again – in another country.

Here he is, having moved to Edinburgh. He would stay there some time.

The 1896/97 Scottish Electoral Register gives his address as 47 Comely Bank Place, north west of the city centre and not far from the Royal Botanic Gardens.

In this game from 1899 he overlooked a tactic.

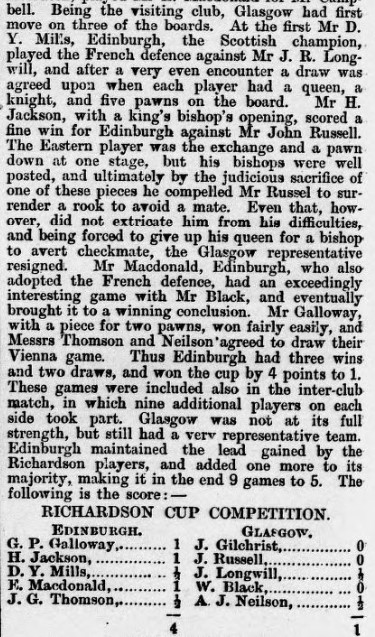

In 1901 Harry was part of the Edinburgh team which won the Richardson Cup (Scottish KO Championship) for the first time.

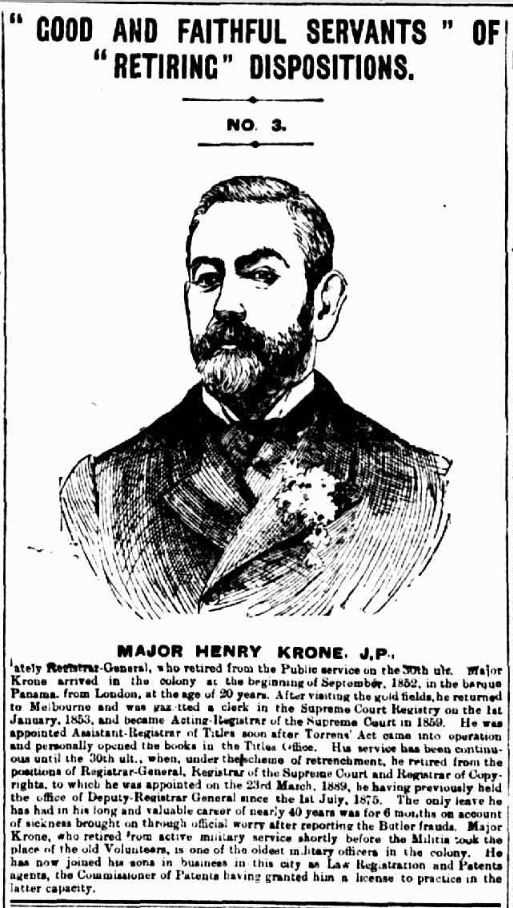

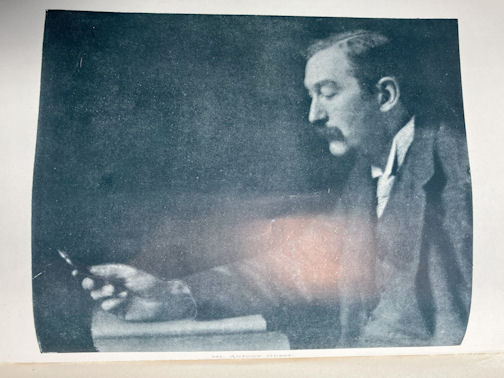

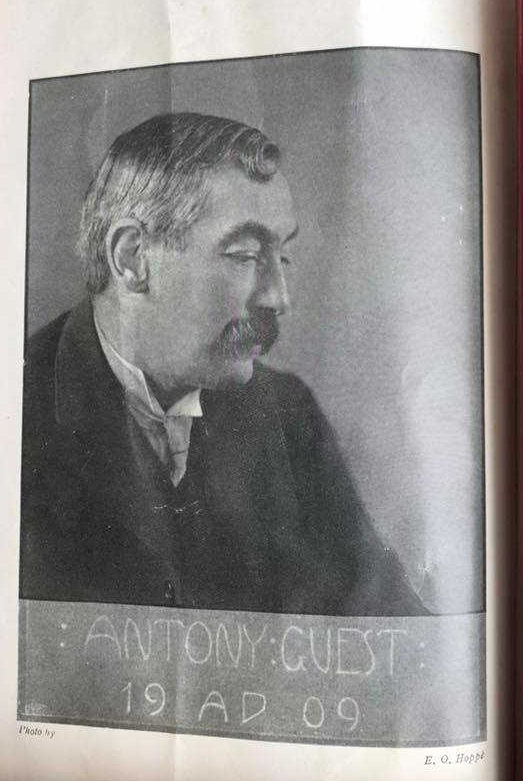

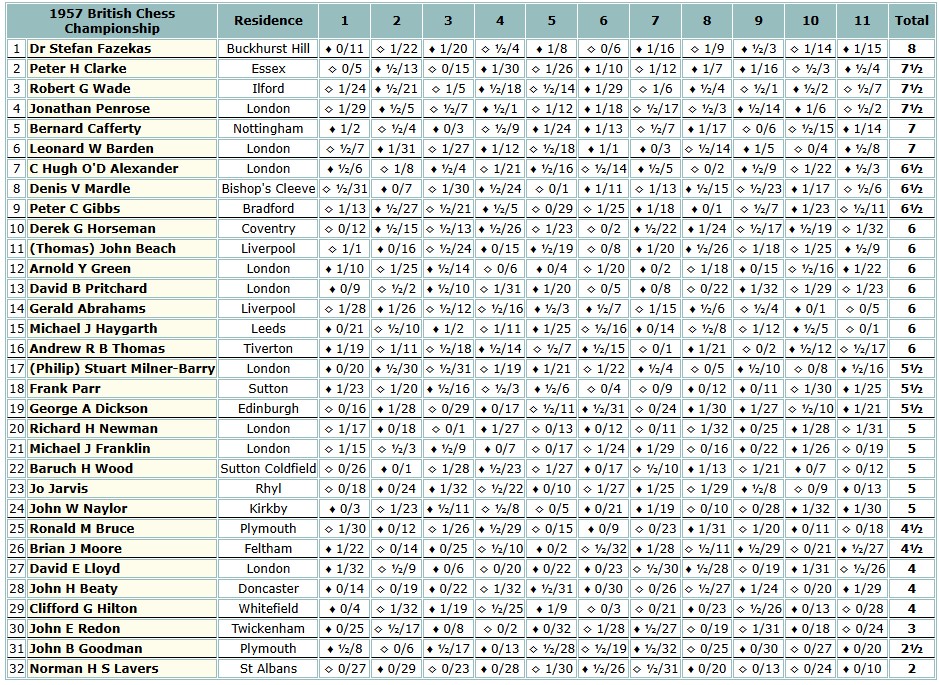

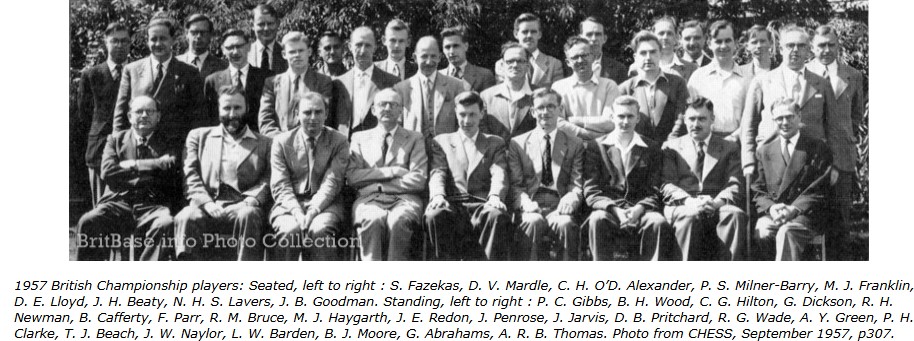

And here, thanks to Edinburgh Chess Club, is the winning squad.

Harry Jackson is the burly (like his father) gentleman second from the left.

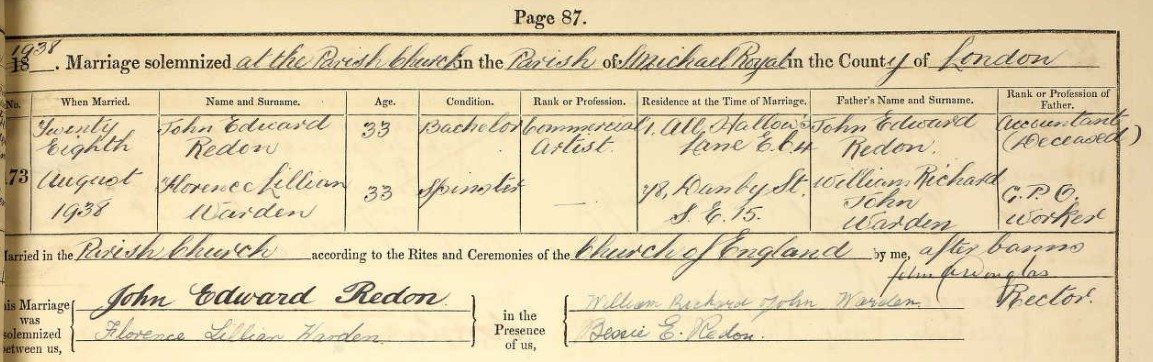

There’s no sign of Harry in the 1901 Scottish (or even the English) census. However (thanks to Alan McGowan for the information) he was in the 1901 Irish census, in Cork. He gave his occupation as a Commercial Traveller (Glass) and was living in a boarding house along with a number of other commercial travellers. He also said that he was married, but there was no sign of his wife.

In 1902 Edinburgh started two correspondence games against their counterparts in Rome, with Harry being one of the team.

Here’s the game in which Edinburgh played the white pieces, which concluded in early 1905.

Harry’s opponent in this game was an important figure in Scottish chess. The rather unimpressive 1. d4 d5 2. Qd3, which had been tried once by Pollock, seemed to have been his usual choice with White at this time.

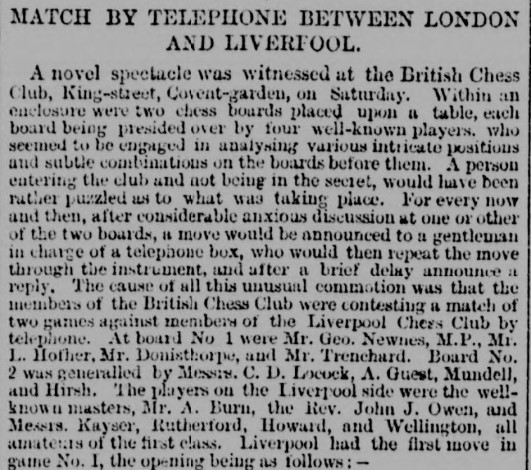

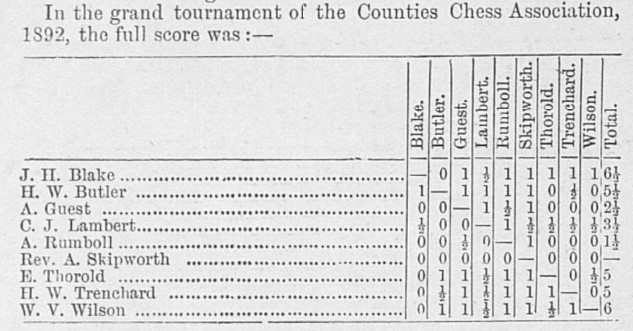

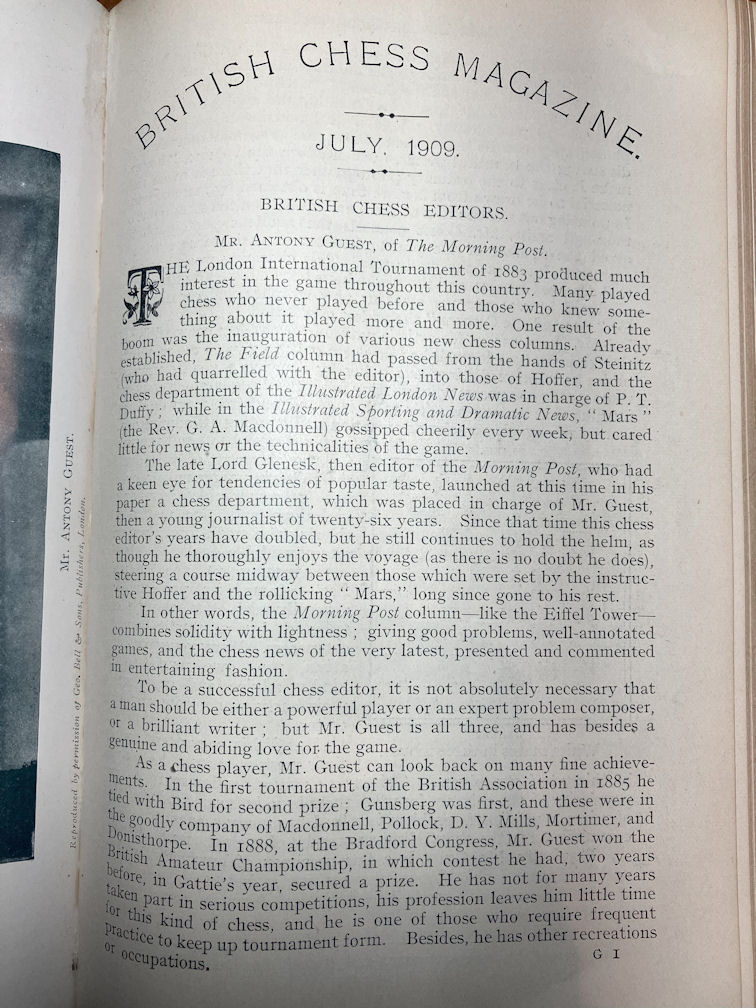

Archibald Johnston Neilson might be considered Scotland’s answer to Antony Guest. He contributed an excellent column, usually twice a week, to his local paper, the Falkirk Herald, for 47 years, from 1895 right up to his death in 1942.

Perhaps he chatted with Harry after the game, asking him to contribute some problems. Since his early enthusiasm between 1879 and 1881 he had only composed occasionally, but now he entered the most prolific period of his chess problem career. For the next three years he regularly contributed problems, not just to the Falkirk Herald but also to the Mid-Lothian Journal.

His games from this period shine a light on both Harry’s strengths and weaknesses.

He could lose horribly when his opening went wrong, as in these two games. You’ll see in the first game that, although he was an Edinburgh player, he sometimes represented Glasgow in matches against English club. (Coincidentally, a Scotsman with the same name as his English opponent here wrote an excellent book on the King’s Gambit some years ago.)

Given the opportunity, Harry could demonstrate skill in the ending: another couple of games.

By way of contrast, here’s an exciting game featuring opposite side castling with both kings seemingly in danger.

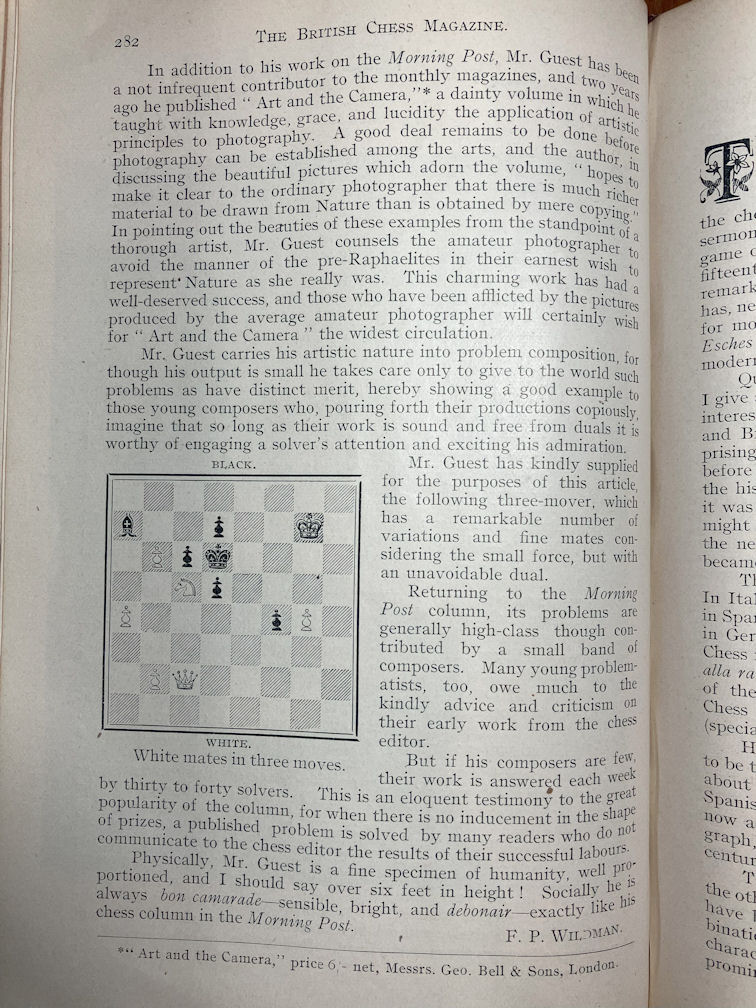

Now for a few of his problems from this period of his life.

Problem 3. #2 Mid-Lothian Journal 21 Apr 1905

Problem 4. #3 Falkirk Herald (for Stirling solving contest) 15 May 1905

Problem 5. #2 Falkirk Herald 31 May 1906

To conclude, an easy one with a very familiar theme.

Problem 6. #3 Falkirk Herald 24 Apr 1907

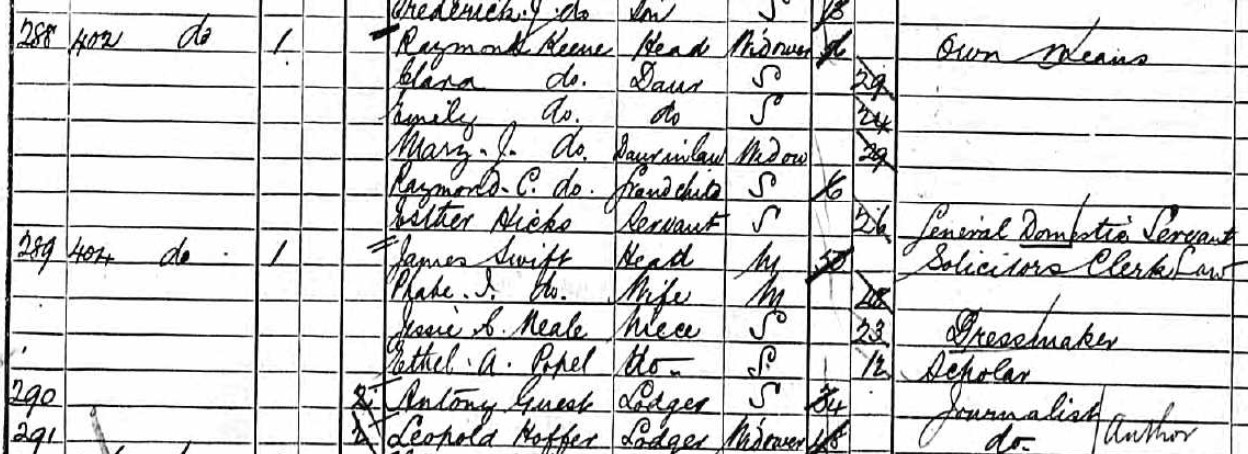

The year 1911 brings us a surprise. Harry isn’t in the Scottish census, but turns up in the English census, in Salford, near Manchester, visiting John Harry Leyland and his family. He’s aged 47 and working on his own account as a dealer in glass bottles. Perhaps there’s some connection there with his brother William, who was also in the glass business. He also has a wife, Ellen, aged 43: they’ve been married 17 years with one child, who is still alive, but not on the census record. Later records will tell us that their child’s name was May.

It’s a reasonable guess that Ellen, also known as Nellie, was related to the Leyland family, and we can locate an 1867 birth record which matches. The family were from Lancashire, but spent the first few years of their marriage in Smethwick. There’s no marriage record for Harry Jackson and Ellen Leyland from round about 1893-94, but there is one from 1902 in Chorlton, not all that far from Salford, so I’d guess that was where and when they married. There’s also a birth record for May Leyland in York in 1895 (no mother’s maiden name given), which was about the time he moved from York to Edinburgh. It seems like Harry and Ellen had had an affair, and perhaps the birth of their daughter prompted them to move to Scotland. They only got round to getting married some years later. Although we know Harry was on the 1901 Irish Census, I haven’t yet been able to find Ellen/Nellie and/or May on any of the England and Wales, Scottish or Irish census for that year.

Harry seems to have been back in Scotland by June, when he was elected one of the vice-presidents of the Scottish Chess Association. He was in august company: one of his fellow VPs was future Prime Minister Andrew Bonar Law.

In February 1912 he returned to the Edinburgh team after an absence, facing Percy Wenman of Glasgow in the Richardson Cup final, the game being drawn on adjudication.

And that he seems to have taken a long break from chess, and it’s not for almost a decade that we pick him up again.

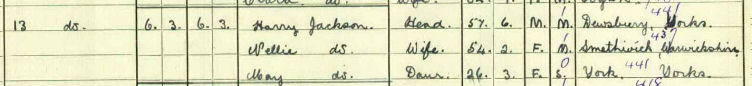

The 1921 Scottish census goes some way to confirming my suspicions.

Here we have Harry, 57, born in Dewsbury, Nellie, 54, born in Smethwick, and May, 26, born in York. Harry was still working as a glass dealer on his own account, while Nellie and May were engaged in household duties. Their address was 13 South Charlotte Street and their residence, right in the city centre, just off Princes Street very close to the castle, had six rooms. Harry’s glass dealing business must have been very successful: not bad for the son of a painter and decorator from Dewsbury.

After an absence of more than a decade Harry returned to the fray in 1923, continuing to play until late the following year, when, perhaps for health reasons, he retired from competitive chess.

Again there was an unexpected move: back to London. They may have been somewhere else first, but in 1927 Harry and Nellie showed up on the electoral roll in Hampton Wick, which is just over Kingston Bridge. Their address was 1 Garden Cottages, Park Road, which, I suspect is where Ingram House is now, just across the road from the Timothy Bennet memorial and a gate into Bushy Park.

This was one of a pair of cottages: number 2 was occupied by John and Unity Chatterton: the unusually named (after her mother) Unity was Nellie’s sister, and it seems the families must have moved there at the same time.

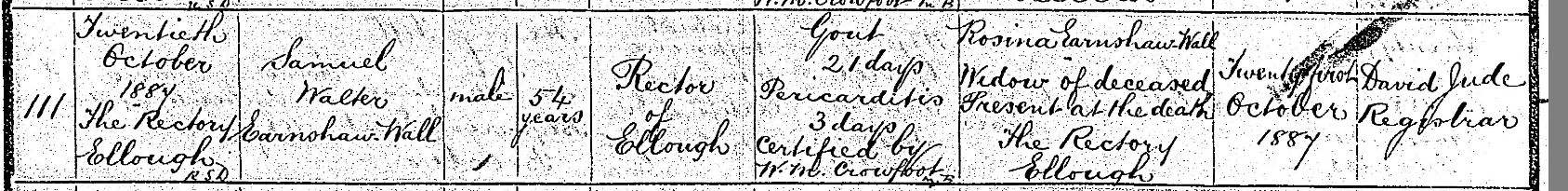

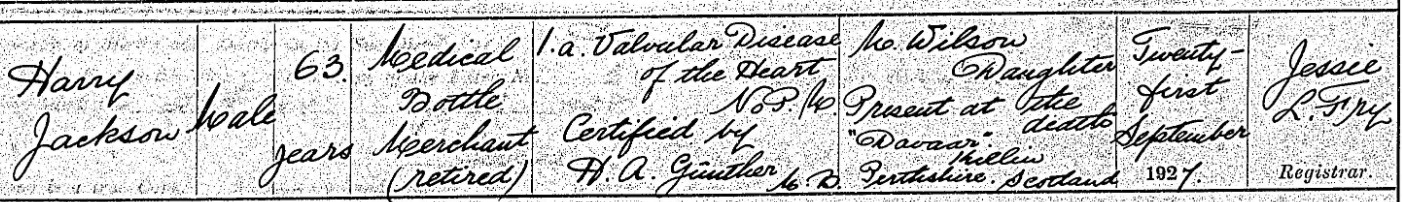

He didn’t stay there very long, though, dying of heart disease just a few months later.

The death record tells us he had been a Medical Bottle Merchant, perhaps acquiring them from his brother William’s company and selling them to hospitals, pharmacies and doctors. His daughter May had travelled down from Scotland where she was living in a remote village on the shore of Loch Tay with her husband, William Eric Graham Wilson.

His old friend Archibald Neilson wrote an obituary.

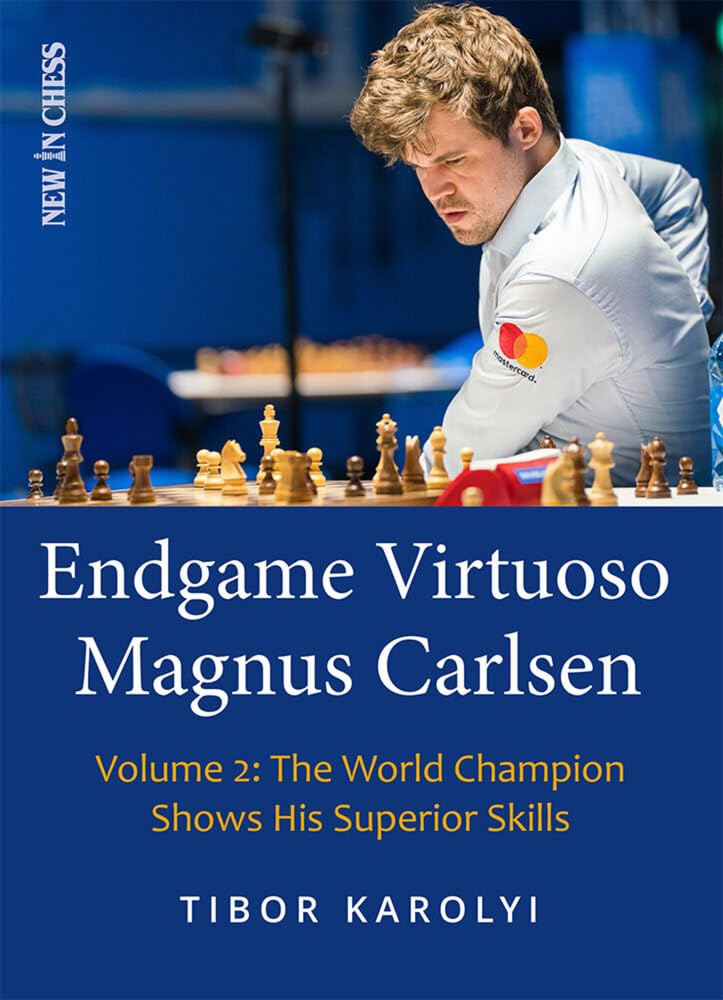

The British Chess Magazine noted his death in October, and published this obituary in November.

You’ll note that they mistakenly called him Henry rather than Harry, the same error they would make a few years later by calling Fred Yates ‘Frederick’.

“A fine and striking personality, he was of a reserved, if not shy, disposition.” “Generous to a fault, and of a quiet and modest demeanour.” A fine way to be remembered by your friends. In the words of the cobbler Timothy Bennet, whose memorial stands opposite where Harry spent his last days, “I am unwilling to leave the world a worse place than I found it”. I’d like to think Harry Jackson would have approved.

Blackburne’s prophecy wasn’t quite fulfilled, but he was still one of the best players around, first in Yorkshire, and then in Scotland. If he hadn’t hampered himself by playing ‘certain bizarre moves in the opening’ he might have ranked higher still. He was also a skilled and, at times, prolific problem composer.

Nellie, John and Unity were still in Garden Cottages in 1928, and by 1929 John and Unity’s son, also John, had reached voting age. By 1930, though, both cottages were in different ownership.

One further thought: in 1928 a new shop opened not very far from there. Perhaps Nellie walked up the road for a few minutes, turned right into Bushy Park Road, crossed the railway line over the level crossing (there’s a footbridge there now) and, coming to the end of the road, visited the Ham and Beef Store owned by the Misses Ada and Louisa Padbury to stock up on provisions. Perhaps she saw a young girl there as well: Ada and Louisa were juggling running the shop with bringing up their irresponsible sister Florence’s illegitimate daughter Betty. (Nellie, the mother of an illegitimate daughter herself, would have been sympathetic.) Perhaps John Chatterton, who was a schoolmaster, taught at the local primary school she attended. Perhaps the family also worshipped at St John the Baptist, Hampton Wick, just a short walk from their homes in the other direction. This was the church where, two decades later, Betty would marry, and where her older son would be baptised. Many years further on, he would tell the story of the chess career of Harry Jackson, the Yorkshire Morphy.

Another coincidence: Unity returned to Lancashire, dying in Ormskirk in 1961. At round about that time, Betty and her family visited Ormskirk, where her favourite cousin Marion, the bridesmaid at her wedding, lived for many years.

It’s another golden thread that binds us all together.

If you’re interested in my file of Jackson family games and problems, let me know and I can send it to you. If you have any more information about this family, I’d love to see it and perhaps incorporate it in this article. And don’t forget to join me again soon for some more Minor Pieces.

Problem solutions

Problem 1.

Problem 2.

Problem 3.

Problem 4.

Problem 5.

Problem 6.

Sources and Acknowledgements

I thought this might be a quick article to research, but it turned out to be anything but. You have someone with a common name who moved around quite a lot (Yorkshire, London, Edinburgh) and disappeared from the records for a time. There are a lot of traps for the unwary and I hope I’ve avoided most of them.

Steve Mann’s Yorkshire Chess History is excellent on the Jackson family in Yorkshire, but doesn’t pick up Harry’s time in Scotland. Rod Edwards (EdoChess) picks up most of his English results, including some of his London matches, but attributes at least one to a totally different Jackson, and also doesn’t record his Scottish results. His Scottish problems are not to be found in the online collections I’ve consulted, which sometimes give him a non-existent middle initial: HS Jackson. Confusingly there was also an HB Jackson from, of all places, Fiji, submitting problems to the Illustrated London News in the late 19th century, some of which have been incorrectly attributed to Harry. This was the unrelated Henry Bower Jackson, whose aunt was married to a distant cousin of Edmund and Eliza Thorold. He in turn was seemingly not related to Sir Henry Moore Jackson, who became Governor-General of Fiji in 1902.

ancestry.co.uk

findmypast.co.uk/British Newspaper Library

Scotland’s People

Yorkshire Chess History (Harry Jackson here)

Alan McGowan (Chess Scotland historian/archivist)

New in Chess (Edinburgh CC 200th Anniversary here)

EdoChess (Rod Edwards: Harry Jackson here)

BritBase (John Saunders)

ChessBase/Stockfish 17

Yet Another Chess Problem Database (Harry Jackson here)

MESON chess problem database (Harry Jackson here)

Google Books and Hathi Trust Digital Library (Chess Player’s Chronicle)

British Chess Magazine November 1927

Geoff Steele website